Bursary Reports 2009

Leila Bassir

Well, finally my first year has come to an end, and as requested, I would like to write and thank you for the bursary granted to me last year, and tell you a little about how I am getting on here at Swansea Medical School.

So, firstly, may I thank you most sincerely for accepting me for and granting me the graduate bursary last year, as my parents were both affected by the economic downturn, it was a great help not just for myself, but also a relief of pressure for them.

My first year at Swansea has passed very well. I thoroughly enjoyed every moment of the course, and am very pleased with my exam results. As I wrote at the beginning of the year, anatomy has continued to be my most enjoyable subject, though unfortunately it is no longer on our curriculum, but neuroscience has taken its place as the next! Throughout I have found myself helped by the knowledge gained through my previous degree, which fortunately covered a lot of ground in clinical skills, and as we have now begun our ward visits, I have a chance to hone them upon actual patients.

This year has begun with quite a jolt compared to the last and

promises to be an interesting one. Last week, within the space of

48 hours, in fact, I found myself the Prince’s Foundation for

Integrated Health Student Network Champion for Swansea, and I only

replied to the email out of curiosity! Besides this, together with

my colleague and selected champion for the Cardiff branch of our

course, we are hoping to build an integrated health network within

the university itself, working with both staff, students, medical

and CAM professionals. Below is a list of the aims and objectives

for our intended project:

Foster an acceptance that many patients use CAM and thus it is

necessary for all doctors to have an understanding of how the

therapies work.

Understand the mechanism of action of different types of CAM, their

side effects and potential interactions with conventional medicine

Promote open communication between CAM practitioners and doctors

Practical advice on how a doctor would access information about the

potential interactions between conventional medicine and CAM

Gain an insight into the practice of both medically trained and lay

practitioners within a given CAM speciality

Expose students to practitioners who have used CAM and conventional

medicines in an integrated fashion

As part of this project we hope to find speakers to discuss the use of CAM and integrated medicine, including both lay and qualified practitioners in order to provide an insight into the spectrum of usage likely to be encountered, and hopefully, medical practitioners who use CAM or practice integrated medicine. Our main goal, not to create an argumentative rally of should it be used or not, but fostering the fact that as doctors, we will encounter patients using other therapies and as such it is best that when faced with a ‘what do you think, Doc?’ that we know a little of what they are talking about.

Besides the above project, I have also been involved in the creation of a new Medical School students’ magazine, both as lead typographer and contributor, and I would have included a first copy, but some of the authors made a decision to alter articles last minute, whilst I was unfortunately not around. My name is still on the page as typographer, however, so if you would like a copy, ... I didn’t do it!

Right now, although I am enjoying everything, I still have no idea what I would finally like to do. I started off torn between rural GP, cardiology, neurology or surgery. Half way through, I had doubts on the surgery. Currently, it stands at GP, neurology or anaesthetics, whilst a lot of my colleagues say they can see me as general practitioner. I do know, that I would like to be able to combine a little minor surgery into general practice, so A &E or rural GP are top of the list. I still have several years though till the final decision, and I am sure our ward placements this year, and our two years clinical in Cardiff should help me make up my mind; and, four years ahead is a very long time, whilst, four years previously, I had no idea I would even be contemplating studying medicine!

Leila Bassir

Katie Levitt

An elective in the Caribbean, an experience of healthcare in two developing countries

Details of Venues and health and safety: I spent a month at St Ann’s Bay Hospital, Jamaica and a month in Victoria Hospital, St Lucia. My supervisors at the institutions were:

Jamaica Dr Horace Betton St Ann’s Bay Hospital, St Ann’s Bay, Jamaica, West IndiesSt Lucia Dr Elisabeth Lewis Victoria Hospital, Castries, St Lucia, West Indies

Main Report:

Aims and Objectives

The main aim of my elective was to experience healthcare provision in two developing countries. I wanted to contrast the healthcare provision, practice and attitudes towards health between the Caribbean and the UK. I was interested to gain the views and beliefs of patients and doctors in a foreign country to broaden my cultural horizons. I was also interested in learning about how healthcare is provided in these countries in contrast to the National health framework used in the UK.

Whilst abroad I wanted to challenge myself to learn medicine in an unfamiliar and self directed environment. I felt it very important to learn how to adapt to a new environment whilst continuing my learning; a skill I will need to implement when I begin my foundation year training.

I am now going to talk about the month I spent in each country separately, beginning with Jamaica.

Jamaica, September 2009

"It is the fairest island eyes have beheld; mountainous and the land

seems to touch the sky”

Christopher Columbus, 1494 (1)

Jamaica is famous for having the most churches per square mile of any other country in the world. Ironically it is also famous for being a violent country, with an estimated 3 murders occurring per day. The official language of Jamaica is English and most correspondences are written in Standard English. However, the Jamaicans have developed their own spoken language, Jamaican Creole or Patois, which is a mixture of African and English. I soon discovered that patois is very different to the English language and would take some getting used to. I had a month to practice the language and learn about the culture in the St Ann’s Bay hospital, St Ann’s Bay where Columbus had landed many years earlier.

One of my first experiences in the hospital was that of a paediatric ward round. The paediatric ward, like all of the others, was nothing like the ones in England. They were all free standing buildings with windows without glass but shutters instead to keep the ward cool. Patients were crammed in to available spaces wherever possible, despite the number of curtains. Cleaning staff kept the ward generally clean, but not up to UK standards. Cobwebs were still visible in the corners of the rooms and dust had settled on the windowsills. Despite this all of the patients seemed generally happy and comfortable.

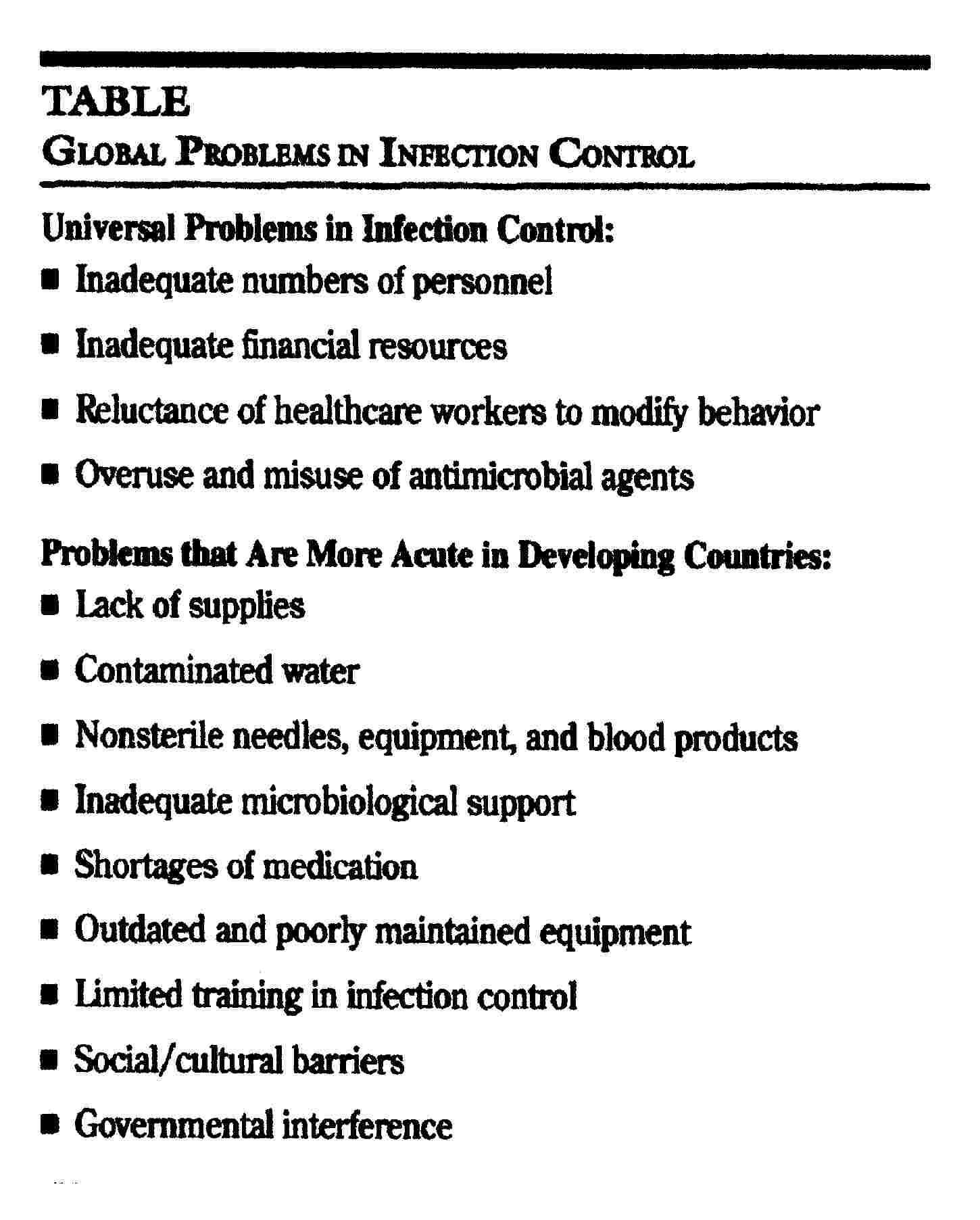

The first thing I noticed as we began the ward round is that the doctors do not wash their hands after each patient contact. Infection control in the form of hand washing is not as strictly implemented as in the UK. The doctors and ward staff can wear rings, watches and long shirts to work in; items banned in the UK due to the bare below the elbows policy. The doctors did not seem aware that the practice of hand washing was important in reducing the spread of infection. In the UK hand washing is so highly publicised and now the cultural norm. I assumed that the same practices would occur all over the world, based on clinical evidence. It was reported by the National Audit Office that hospital acquired infections could be reduced by 15% with correct hand hygiene (2). The lack of hand washing could be attributable to shortages or lack of cleaning products in the country. This has been identified by a paper looking at infection control globally. The table opposite shows just some of the problems that developing countries like Jamaica face relating to the implementation of infection control practices. The paper suggests that developing countries may be aware of the practice of infection control but do not have access to the training or funding to implement this practice (3). When I asked doctors about hand washing they were all familiar with the practice but were not strictly told to implement it. This experience, although a surprise, has shown me that healthcare is affected by many factors; money, culture and evidence based best practice are some of these. I was beginning to understand some of the difficulties and barriers that developing countries face to provide good healthcare.

The second thing that caught my attention on the ward round was the doctors’ lack of communication. It was the norm to stand around the end of the patient’s bed and talk about their history and condition without involving them in the conversation. This was often done without a curtain drawn around the bed, even when a physical examination was conducted. Usually once a management plan had been decided upon the doctor would communicate this to the patient or parent very bluntly and then move on. I found this lack of communication unsettling. From our first day of clinical practice we have had the skill of communication put at the centre of becoming a great doctor. Poor communication may be part of the culture in Jamaica, but it is very upsetting to observe. This experience has taught me the value of effective communication. I believe that the patient should always be fully informed, involved with decision making and respected as an individual and will always implement these when dealing with patients in the future

The St Ann’s Bay hospital is a Government run establishment. Despite this service users have to pay fees to the hospital for all medications, specialised investigations and for transportation, including an ambulance service. A ‘friends of the hospital’ group arrange fundraising events to raise money for the hospital to help subsidise the cost of care for those who cannot afford it. The experience of this provision of healthcare has made me appreciate the greatness of the UK’s ‘free’ National Health Service. All who require healthcare in the UK have access to it, unlike in Jamaica where if you cannot afford to pay you do not receive the care.

This was demonstrated whilst on a medical ward round. I met an elderly lady who had been admitted with a suspected stroke. The medical team looking after her wanted to get a CT scan of her head to confirm the pathology and diagnosis. However she had very little money to pay for the scan and her family were unable to help. This meant that the diagnosis was not confirmed by a CT scan and the extent of the damage to her brain remained unknown.

There is no doubting that the Jamaican culture is a rich, diverse and dynamic one. Part of the culture involves a very paternalistic idea of healthcare. Doctors are seen as the ones with the medical knowledge and should always know what is best for a patient. Patients trust and respect the doctor’s advice. This is a vast contrast to the UK. We are moving towards a shared doctor-patient relationship, one in which the patients help in the decision making process of healthcare. Most patients in the UK like to be well informed of their medical condition and health and have a say in what is best for them. I was shocked to see this ‘traditional’ model of healthcare and how popular and happy patients were with it.

This paternalistic model of healthcare does have its downfalls. Patients are reliant on the doctor to manage their conditions and patient education, a vital component of healthcare, is often missed out. This was demonstrated by the high prevalence of type 2 diabetes in Jamaica; estimated to be 17.9%, the highest out of all the Caribbean islands (4). The Jamaican diet is high in sugars and fats, leading to obesity and the problems related with this. On the surgical wards I saw many patients who had been admitted with the complications of type 2 diabetes. Many had large, infected diabetic ulcers that required debridement. Some were so extensive that it had led to the complete loss of a foot or limb. I was disturbed as to how many patients had these drastic complications of the disease. It seemed that education about medicines and diet had not been successful and patients were unable to manage their own conditions. This experience has taught me just how vital it is that patients gain an understanding of their own health and how to best manage it. As a doctor I will take time to do this for my patients

St Lucia, October 2009

St Lucia is a smaller Caribbean Island, situated farther South and East of Jamaica. It is part of the British Commonwealth and the Queen still appears on all local currency. Like Jamaica, St Lucian’s are extremely proud of their culture. I was lucky enough to experience Jouen Kweyol (or Creole Day in English) a cultural festival that celebrates the local food and national dress of St Lucia. The official language of St Lucia is English, but the spoken language mixes French, English and African to create a unique patois language. Like Jamaican patois, it was incredibly hard to understand and would require yet more practice in the Victoria Hospital, Castries to learn.

The Victoria hospital is a public, government run hospital that serves a population of 100,000 people. It is the larger of two hospitals on the island. At the time I was on placement in St Lucia a fire had swept through St Jude’s, the other public hospital on the island, which meant that the workload had considerably increased for all of the staff at Victoria. Although the hospital was a public one all patients that visited had to be covered by health insurance to pay for the costs, much like the system in the United States. A doctor explained to me how it was very common practice for a patient to provide the incorrect contact details so that they cannot be traced after leaving the hospital. The Government then clear the cost on behalf of that patient. This is a new way of cheating the healthcare system in the country that is becoming more popular with residents who cannot afford medical treatment.

My chosen rotation in this hospital was gynaecology. As part of the gynaecology rotation I spent a morning in surgery. There were two operating theatres in the hospital; one was specifically designated to obstetrics and gynaecology cases. There was a small recovery area between the two operating theatres and a corridor outside the theatre that was used as the waiting area. The operating theatres themselves looked out onto the Castries harbour with spectacular views. They were well equipped with the necessary modern technology, as used in England, but they did lack the laminar air flow mechanism which prevents the settling of organisms in the operating theatre and reduces post-operative wound infection (5).

I observed a caesarean section in surgery. The one thing about this operation that I will always remember is the poor communication with the patient. This lady was visibly distressed and anxious whilst waiting outside the operating theatre and at no point did any member of staff reassure her that everything would be ok. This was displayed again when the anaesthetist was speaking over the patient whilst she was being cleaned and draped for the procedure. It would seem that this is the culture in this country; one similar to Jamaica. Poor communication was demonstrated time and again whilst on ward rounds in the hospital. As a future doctor I feel that keeping the patient central to care and maintaining their dignity and respect is crucial. Observing this situation has made me realise just how important learning how to communicate well is and this is something I will strive to achieve throughout my career.

Throughout my time in the Caribbean I have witnessed the presentation and treatment of tropical diseases that I would not have done in the UK. I have seen patients with rheumatic fever, sickle cell disease and many strains of Tinea. The rarity of these conditions in the UK motivated me to learn about them whilst out in the Caribbean. It was useful to relate the written textbook presentation of these illnesses to a real life scenario. I now feel that I have gained more knowledge of tropical illness and disease through firsthand experience of the conditions.

Conclusions

Experiencing healthcare provision in a completely different and diverse setting has been a highlight of my training so far. I wanted to gain a perspective on how healthcare is provided in developing countries and how it encompasses the culture and beliefs of patients and doctors. I feel that this has been successfully achieved. Through observation and involvement with the doctors who are providing the care in these countries I learnt about their attitudes to health. I was also able to gain an insight into the structure of their healthcare system in each country and compare this to the structure in the UK. Having the opportunity to learn about a culture that is very different to our own has been a vital part of this experience. I now feel more confident in dealing with patients in hospital who may be from a different culture or religious background to my own. I learnt to respect and adopt their culture during my time abroad, an aim that I wanted to achieve.

In conclusion, the experience of another countries healthcare system has been challenging yet rewarding. It has shown to me just how advanced healthcare provision is in the UK and how lucky we are to receive such good healthcare and modern facilities. I have learnt about barriers to healthcare provision in a developing country and the challenges that doctors in those countries experience.

References

1. Discover

Jamaica, Geography

http://www.discoverjamaica.com/gleaner/discover/geography/geography.htm

2. Hand

Hygiene. Use of alcohol rubs between patients: they reduce the

transmission of infections. BMJ 2001. August 25;323(7310):411-412

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1121017/

3. Global Aspects of Infection Control, Mary D. Nettleman, Infection control and hospital epidemiology, Vol. 14, No. 11, (Nov 1993), pp 646-648

4. Incidence and Prevalence of Diabetes in the Americas, Alberto Barcelo and Swapnil Rajpathak, Rev Panam Salud Publica/Pan Am J Public Health 10(5), 2001.

5. Rheumatic Fever, pp76-77, Clinical Medicine, Kumar and Clarke, 2005 Elsevier limited

6. An

overview of Laminar Flow Ventilation for operating theatres,

Queensland Health, October 1997.

www.health.qld.gov.au/cwamb/cwguide/laminar.pdf

Katie Levitt